When the last machinist who knew how to calibrate the 1970s equipment retired, production ground to a halt for three weeks. The company had the manual somewhere, but nobody could find it among thousands of scattered documents. This knowledge crisis, repeated across industries, sparked the evolution of enterprise knowledge management from necessity, not innovation.

Understanding the history of knowledge sharing reveals why growing companies can’t afford to repeat these costly mistakes. From ancient civilizations carving complaint records into clay tablets to modern AI-powered knowledge platforms, the quest to capture and share institutional knowledge has driven organizational success for millennia.

The foundation years: when knowledge lived in people’s heads

Pre-digital knowledge sharing relied on human memory and physical documentation. Master craftsmen in medieval guilds spent decades training apprentices through hands-on experience. Later, the Industrial Revolution introduced standardized manuals and procedures, but updating them remained slow and expensive.

The real challenge wasn’t just storage. It was ensuring the right person could access the right information when they needed it. A policy change could take months to propagate through an organization, and version control meant literally stamping “SUPERSEDED” on outdated documents.

According to research, 42% of institutional knowledge is unique to individual employees and isn’t documented elsewhere in the organization. This isn’t a modern problem. It plagued enterprises long before computers existed.

Ancient examples reveal sophisticated approaches to knowledge preservation. We have evidence of customer complaints carved into clay tablets from the ancient civilization of Ur around 1750 BCE, creating some of history’s first customer service documentation. The US Air Force developed the Knowledge-Based Systems Architecture (KBSA) during the early computing era to capture aircraft maintenance expertise. Microsoft had their own knowledge base systems as early examples of getting support for their knowledge base technology.

The Middle Ages had guilds where apprentices would work their entire life with a master to learn how to do something. This was a necessary step before you were allowed to work in that profession.

Things gradually changed after the Industrial Revolution which led to the rise of formalized apprenticeships and mentoring led by workers in the factory.

Traditional pre-digital methods included:

- Paper-based documentation: Companies maintained physical records, such as printed manuals, handbooks, and file folders, to store information about policies, procedures, and best practices

- Filing cabinets and archives: Companies stored important documents and records in filing cabinets, organizing them by department or topic. Larger organizations often had dedicated archives for long-term storage

- Binders and reference books: Companies often kept compilations of important information, such as employee handbooks, standard operating procedures (SOPs), and product catalogs, in binders or printed them as reference books

- Microfilm and microfiche: These film-based storage methods allowed companies to store large amounts of information in a compact format, which could be read using special viewing machines

- In-house libraries: Some larger organizations maintained in-house libraries that housed books, journals, and other reference materials relevant to their industry or operations

While these methods allowed for the storage and sharing of information, they often faced challenges such as limited accessibility, difficulty in updating and maintaining records, and the potential for information silos within the organization.

The digital transformation wave: 1990s to early 2000s

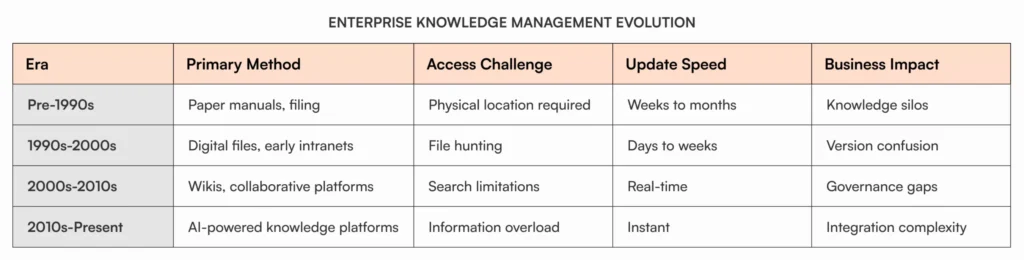

The knowledge management history timeline shows three distinct phases: preservation, digitization, and collaboration. The 1990s marked the beginning of digital knowledge transformation, driven by early intranets and database systems.

Companies rushed to digitize their paper processes, but many simply recreated the same organizational problems in digital format. File servers became electronic filing cabinets. Searchable, but still requiring users to navigate complex folder structures to find information.

Early digital adoption faced significant hurdles. According to Harvard Business Review research, workers toggle between applications nearly 1,200 times daily, spending approximately four hours per week just reorienting themselves after switching contexts. This context-switching problem emerged as companies adopted multiple disconnected digital tools.

The collaborative revolution: enterprise wikis transform knowledge sharing

The knowledge management history took a decisive turn in the mid-2000s with collaborative platforms. Here’s a detailed timeline of how enterprise internal wikis evolved:

1995 – Ward Cunningham develops the first wiki software, WikiWikiWeb, to facilitate collaborative document creation and sharing among programmers.

1999 – Jive Software is founded, which would later become a major player in the enterprise collaboration software market, offering tools like internal wikis.

2001 – Wikipedia, the world’s largest online encyclopedia, is launched, demonstrating the power of collaborative knowledge sharing on a massive scale.

2002 – Socialtext, one of the first enterprise wiki platforms, is founded, providing businesses with a tool to create and manage internal wikis.

2004 – Atlassian launches Confluence, a popular enterprise wiki and collaboration platform that gains widespread adoption in the following years.

2005 – Microsoft introduces SharePoint, which includes wiki functionality as part of its enterprise content management and collaboration suite.

2006 – IBM releases Lotus Connections, an enterprise social software platform that includes wikis as a core feature.

2007 – Google launches Google Sites, a free wiki and web page creation tool, which is later incorporated into Google Workspace (formerly G Suite).

2008 – Wikis gain increasing popularity in enterprises as a means of internal knowledge management and collaboration.

2010s – Enterprise wiki platforms continue to evolve, integrating with other collaboration tools like chat, task management, and document sharing.

2013 – Atlassian goes public, reflecting the growing demand for enterprise collaboration software, including wikis.

2018 – Notion, an all-in-one workspace that includes wiki-like functionality, gains traction among businesses and individuals.

2020s – The COVID-19 pandemic accelerates the adoption of remote work and digital collaboration tools, further highlighting the importance of enterprise wikis for knowledge sharing and teamwork.

Throughout this history, enterprise internal wikis have evolved from simple collaborative document editing platforms to integral parts of comprehensive enterprise collaboration suites.

As enterprise wikis matured, organizations learned that technology alone wasn’t enough. Success required governance, user adoption strategies, and clear content standards. Implementing best practices became essential for companies wanting sustainable knowledge management systems.

What most executives missed during the early wiki adoption was that collaboration without governance creates more chaos, not less. Companies that succeeded treated knowledge management as a business process, not just a technology deployment.

Even with digital platforms, companies discovered new obstacles. Information became easier to create but harder to maintain, leading to digital decay and content sprawl. These sustainability challenges help explain why many early knowledge initiatives failed within two years.

Departmental knowledge management: specialized solutions emerge

Different departments developed distinct approaches to institutional knowledge preservation based on their unique requirements and regulatory pressures.

Human Resources departments became early adopters of structured knowledge management, driven by compliance requirements and the need to standardize policies across growing teams. HR-specific knowledge management became critical as companies scaled beyond 50 employees.

The challenge intensified as regulations like Sarbanes-Oxley and HIPAA demanded both security and accessibility. Balancing document security with usability became a defining characteristic of enterprise-grade knowledge platforms.

According to the Society for Human Resource Management, it takes new hires 8-12 months to achieve full productivity in professional roles. This extended ramp-up time drove HR teams to develop comprehensive onboarding knowledge systems that could accelerate new employee integration.

Forces shaping modern knowledge management

While the historical evolution reveals important lessons, several key forces are changing how growing companies approach knowledge sharing today and will define what comes next.

Advanced search capabilities have moved beyond simple keyword matching. Modern platforms can dig into videos, PDFs, and complex documents to find relevant content that used to stay buried in files. What’s coming next? Search that actually understands context well enough to surface the right information before you even finish typing your question.

Artificial intelligence currently helps organize and surface knowledge automatically. AI can spot connections between documents and suggest relevant content based on how people actually work. The real potential lies ahead: systems that will push critical information to the right people at exactly the right moment, without anyone having to hunt for it.

Collaborative intelligence captures the context around information through user interactions. When someone comments on a document or asks questions, that creates valuable insight about how knowledge gets used. Future versions will understand the relationships between people, projects, and information in ways that make expertise transfer much more effective.

Customer insights remain frustratingly siloed in most organizations. Research shows only 49% of business decisions use actual data rather than gut feelings. Better knowledge platforms will automatically get customer research to the people making decisions about those customers.

Lessons for today’s growing companies

The evolution of enterprise knowledge management teaches three critical lessons that every scaling organization must understand.

First, technology alone never solves knowledge problems. The graveyard of failed wiki implementations proves that successful knowledge management requires governance, training, and cultural change alongside the right platform. Companies that treat knowledge management as purely a technology decision consistently struggle with adoption and sustainability.

Second, knowledge systems must integrate seamlessly with existing workflows rather than creating additional overhead. The most successful modern platforms solve business problems first, organize information second. Where paper systems created access bottlenecks, effective solutions provide role-based permissions. Where early digital tools created version chaos, current systems deliver audit trails and approval workflows built into the user experience.

Third, the cost of poor knowledge management compounds exponentially as companies scale. Early investment in proper knowledge infrastructure prevents the costly scrambles that happen when institutional expertise walks out the door with departing employees.

AllyMatter exemplifies this learned approach by centralizing documentation with smart approval flows, granular access control, and comprehensive audit trails. Rather than adding another tool to manage, the platform integrates knowledge management directly into how teams work, with intelligent organization and metadata search that actually helps people find what they need when business decisions hang in the balance.

What’s next: AI and the future of enterprise knowledge sharing

The evolution continues as artificial intelligence transforms how organizations capture, organize, and surface institutional knowledge. Modern platforms use machine learning to suggest relevant content, identify knowledge gaps, and automate routine documentation tasks.

However, the lesson from this evolution is clear: knowledge management platforms must solve real business problems, not just organize information. Growing companies need systems that prevent knowledge loss while supporting rapid scaling.

Most growing companies realize too late that scattered documentation creates expensive bottlenecks. Join our waitlist to discover how AllyMatter prevents knowledge chaos before it slows your growth.

Related Reading:

- Internal Knowledge Base Best Practices

- Building a Future-Proof Internal Knowledge Base

- Internal Knowledge Base Maturity: S strategic Framework

- Why Growing Teams Need a Standalone Internal Knowledge Base

Frequently asked questions

How did regulatory requirements drive knowledge management evolution?

Compliance needs accelerated enterprise knowledge management adoption. Sarbanes-Oxley (2002) required documented financial processes, while healthcare and manufacturing regulations demanded traceable procedures. This regulatory pressure forced companies to move beyond informal knowledge sharing to auditable systems.

Why did early enterprise wikis often fail?

Most early wiki implementations failed due to three factors: lack of governance (anyone could edit anything), poor search functionality, and absence of workflow integration. Companies that succeeded treated wikis as business tools requiring clear ownership, content standards, and user training.

What’s the biggest difference between modern knowledge platforms and early systems?

Modern platforms integrate with existing workflows rather than requiring separate processes. Instead of maintaining a wiki alongside email, chat, and file storage, today’s solutions centralize knowledge within the tools teams already use, with automated workflows and smart search capabilities.

When did knowledge management become essential for growing companies?

Knowledge management transitioned from nice-to-have to business-critical during the dot-com era (1995-2000) when rapid scaling exposed the costs of tribal knowledge. Companies that couldn’t systematize their processes struggled to maintain quality and consistency as they grew.